Charities, Non-Profits, and other Third Sector Organisations are important elements of our civic society; operating in areas where the government (both Local and Central) have either under-served or are not trusted to operate. They are often funded through combinations of private or public grants and have legal protections excusing them from tax obligations. Due to their tendency to work with vulnerable and marginalised groups, and their financial status they are often required to be ‘Transparent and Accountable’ in both their work and spending.

This thesis presents a workplace study account of over three years’ embedded research within a charitable organisation in North East England, with details of additional engagements with other charity sector actors. In the thesis, I outline how ‘Transparency and Accountability’ are accomplished in everyday work practice and I chronicle a design process leading to the development of novel, inter-operable, accountability tools within this setting. These tools were trialled across two charities and then discussed with key financial stakeholders to critically evaluate their efficacy. I then present further implications for designing for ‘Transparency and Accountability’ in charities.

I provide the following contributions. Firstly; an understanding of ‘Accountability Work’ in workplace practice and design requirements for digital systems in these environments. Secondly, a model for the structured representation of everyday charity activities, first as the Qualitative Accounting Data Standard and then, through the implications of its deployment, in modelling commitments and actions. Thirdly; a set of design requirements for systems and interfaces to support the collection and curation of, and interactions with, this data in charities. Finally, I present Vanguard Design as an implementation and critique of participatory design principles in the environment of small front-line charities and contribute lessons for Digital Civics researchers in these contexts.

This thesis is dedicated to Andi, Carl, Dean, Lynne, Mick, Owen, Sonia, Sydney, and the young people of the West End of Newcastle upon Tyne.

In loving memory of Mick, who did so much for so many and asked for so little in return.

Deyr fé deyja frændr deyr sjálfr it sama en orðstírr deyr aldregi hveim er sér góðan getr

Deyr fé deyja frændr deyr sjálfr it sama ek veit einn at aldri deyr dómr um dauðan hvern

It goes without saying that thesis-writing does not occur in a vacuum. Despite a few substantial bumps in the road, I am very glad to be in a position to submit this work and the only reason I am here now is because of the collective efforts of many in helping me. It is impossible to capture in words the deep well of gratitude I have for all mentioned and beyond.

First and foremost; special thanks to my collaborators and participants who took part in this work. Working within the context of The Patchwork Project made me a better researcher, and ultimately made me a better man. I started working there when I was 24 and thus the same age as many of the service users. I am not sure whether Patchwork intended to “do Youth Work” on me, but they did. They made me more collaborative, less anxious about how I appeared to others, and gave me more support than any other single institution involved in this thesis. This thesis is dedicated to them. If I named every young person who made me smile I’d never finish this work, but the 8 - 12 group at Patchy 2 formed some of the warmest and most treasured memories I own. Further thanks to Gateshead Older People’s Assembly and Edbert’s House for participating in the design and deployment. Especially to ‘Heather’, who furnished me with more tea and cake than I could handle during our visits. I cannot thank any of you enough, and I love you all dearly.

Next I wish to thank colleagues and collaborators within Open Lab. Dave Kirk’s herculean supervision efforts in getting this thesis even remotely close to submission cannot go understated. A true mentor and guide, thank you so much. My Digital Civics contemporaries, across the whole CDT, have provided immeasurable laughs and phenomenal guidance across the years. Special mention here must be given to Angelika Strohmayer, without whom I would not have made it through several key challenges. Thank you, Angelika, for being the best desk-mate in the world, helping me through it all, and for sharing my passion for tea. Rosanna Bellini must also not go unthanked. First in her capacity as colleague and Digital Civics researcher she has provided frankly stupendous inspiration and has set the bar very high, it’s truly been an honour to witness her work and share a lab with her. Her second capacity is as a confidante, flatmate, and surrogate sister. In this role she has provided a home for me in every sense of the word. This has involved unceasing support, patience, and familial care. Our kitchen table has been the site of many shared laughs, mutual care, and shared meals. If I had to thank a single person for helping me with this thesis, it’d be Rosanna Bellini.

My comrades in the Communist Party of Britain (Northern District) also need to be thanked; for embodying the importance of practice and disciplined militancy. This taught me much about sitting down and getting the work done. I especially wish to thank Martin Levy and Margaret Levy for the years of hard-learned lessons you manage to make enjoyable and accessible and for improving my reading of key texts and fundamentally making me a better Marxist. I must also thank Emma, alongside whom I’ve waved flags and clashed with fascists on many a rainy Saturday; and whose work as vanguard in the UCU stands as example to all.

My research ended in 2018 and the last two years, while writing, I have found a place and a home with my colleagues and co-operators at Open Data Services Co-operative, who’ve granted me the stability to finish this thesis and meaningful work alongside it. This small group of people have materially enriched the lives of so many, and given me the purpose, flexibility, and stability I needed to get well again and pick up this thesis to finish it. To mention one would be a disservice to all, but thank you all so, so, much.

I have also been lucky enough in the last few years to be surrounded by good friends, extended colleagues, and surrogate family, who have put up with me missing gatherings, and have fed both my body and soul in numerous ways to get me over the finish line. In no particular order thanks must be given to: Stacey McGeorge, Alice Adams, Karen Watson, and Jason Hussein at Goodspace Newcastle; Jack, Hannah, and Maia each of the family Arnstein; Kat da Silva Morgan and Feral Noir; Aga Czarny; Bernadine Fernz; and Alexandra Dent (who has been very patient with me and very supportive these last few months).

It would be wrong of me on many levels not to thank Bethany. You never stopped working to make me feel better, even when I couldn’t see it. I am eternally sorry and grateful, and you deserved so much better.

Finalmente, para Valentina gracias por la orientación, la paciencia eterna y por creer en mí. Te amo.

In August 2015 the charity Kids Company made headline news for coming under investigation for financial mismanagement (Grierson, 2015). Founded in 1996, it was one of the most recognised and celebrated charities in the UK at the time, and was set up to provide support to deprived children and its founder Camila Batmanghelidjh regularly featured in lists of influential people and her portrait hung in the national gallery (Renegade Inc, 2017). Its financial activities were widely publicised, and the organisation closed its doors soon afterwards (Elgot, 2015).

Kids Company was an incredibly wealthy charity, attracting ~£23m in 2013 (Charity Commission for England and Wales, 2021b; Bright, 2015), and the UK government had recently granted it a single grant worth £3m which it was now seeking to recover. The Guardian reported that Kids Company had burned through two financial directors in less than three years (Laville et al., 2015). The BBC reported that the organisation had received up to £46m of public funding, including 20% of the Department of Education’s grant programme in 2008 (BBC News, 2015). Camila Batmanghelidjh has since stated that the charity was actually audited 46 times since its inception, and that they were short of money because they’d built a solid reputation with the kids on the street that they helped which lead to surges in numbers (Renegade Inc, 2017). Kids Company itself was set up to address deprived inner-city children and the charity has claimed a high volume of direct beneficiaries within the region of 36,000 children per year, although that number was disputed (Ainsworth, 2015).

Kids Company serves as a very public example of contemporary opinions around charity and non-profit work and spending. Charities are asked to be “Transparent and Accountable” (Oliver, 2004; Dhanani, 2009) for both their actions and their spending. Charities find themselves playing an important role in society taking up the slack in areas where the private sector and government can either not be trusted or simply do not care to spend attention (Hansmann, 1980), and their actions are critical to generating and sustaining ‘Social Capital’ (King, 2004; Wang & Graddy, 2008); the shared skills, trust, and relationships within society which can determine its efficiency and character (Field, 2003). Operating in this space means that they are often trusted with grant money from both public bodies and philanthropic trusts, and often work with vulnerable people and groups in sensitive contexts. This can lead to things going wrong in ways that are potentially far worse than mis-spending project funds (Ratcliffe, 2019).

In the UK’s age of austerity the performance of this work is essential; Local Authority budgets have been continuously slashed and charities have stepped in to fill the gaps in service as the government withdraws its support. Any charity trusted with public funds has a hard job to do; making every penny count while trying to provide services on-the-cheap that have traditionally been the remit of Local Government. All of this places charities at an interesting, and precarious, intersection of being Accountable to large swathes of the population and a variety of stakeholders. Each of these stakeholders then demand their own forms of Transparency and Accountability (Koppell, 2005). Transparency and Accountability, however, are words that are often invoked but rarely defined (Hood, 2006) and these two seemingly simple terms each hide multifaceted, complex, shifting, and interrelated concepts that ultimately mean different things to different people. Charities, and similar Non-profit organisations across the world, thus find their daily work to consist of socially important (if not critical) tasks which they they then must work to account for in a variety of ways to a variety of people. They operate on limited resources as grant funding is increasingly difficult to come by and are increasingly forced to compete for shrinking funding pots (Radojev, 2018). This forces many to twist into new shapes and undergo transformations into ‘Social Enterprise’; a process which risks exposing them to market forces and losing their ability to generate Social Capital by cutting non-profitable services and transforming their beneficiaries into customers (Eikenberry & Kluver, 2004). It is thus the Sisyphean task of charities to perform crucial work on small budgets while wrestling with the hydra of being Transparent and Accountable for every action and every great-british-pound; one slip up could mean public outcry, defunding, and collapse which exacerbates the social conditions that gave rise to them in the first place.

It is during the collapse of Kids Company that I was part-way through the first year of my journey in the Digital Civics programme, and drawing up the plans for my Master’s dissertation study. I now turn to describe how this setting influenced my personal motivations for the study

My personal motivations for this research are the synthesis of the material conditions that were present during my year of MRes study immediately preceding my PhD. These were namely: the collapse of Kids Company and the questions it raised about the role of charities in civic society; and my growth from a Liberal idealist into a dedicated Socialist. I will discuss each of these in turn.

When I began on the Digital Civics programme as an MRes student in 2014/15 I went into the studies with an interest in HCI and Design processes, which were ignited from my undergraduate studies at Newcastle University. I also carried with me a personal dedication to concepts of “openness” which was born of my formative years engaging with the Free Software movement. Throughout the studies of the ‘MRes in Digital Civics’ these interests were refined through engagement with the course material and the contemporary literature. In one interaction my soon-to-be supervisor, David S. Kirk, recommended that I read The Open Source Everything Manifesto (Steele, 2012). I obliged and while I found it a bit new-age in places, I found it lent credence to the idea that open information and Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) could provide the foundation for a strong civic life. This seemed a natural fit for my passion for openness, participatory practices, and the arena of Digital Civics.

Stemming from this, my MRes dissertation originally focused on the consumption, analysis, and presentation of Local Authority data. This broadened my academic focus from the idea of “open” to that of Transparency and Accountability, as it pertained to government spending. By 2015 the citizens of the UK had experienced half a decade of Tory austerity politics which had slashed Local Authority budgets dramatically (Lowndes & Gardner, 2016), and I thought that developing systems to promote use of mandatory spending data to the otherwise-absent “armchair experts” (Cornford et al., 2013) would be a good way to flex my newly-acquired Digital Civics muscles. When Kids Company made the news its presence in the zeitgeist triggered conversations between myself and my supervisor around investigating people’s interactions with charity spending data. Charities are a prime example of a civic space, they do important work, and clearly people feel strongly about how they spend cash and perform work. We thus shifted the focus of the MRes dissertation and I sought participants from within the Charity sector in addition to those with a stake in Local Authorities.

The performance of that initial research made it clear that the local Charity sector were far more willing, and/or capable of engaging with me constructively than actors within the Local Authority. This presented me a much more interesting and fertile space for HCI and design research to effect real change in the lives of communities that had been so adversely affected by austerity. The paper stemming from that initial research (Marshall et al., 2016) showed a sector where various forms of Transparency and Accountability were at odds with each other; and there were opportunities to develop newer, more effective, interfaces and practices around communicating that I was keen to explore.

Throughout this year and study I was also developing my own citizenhood, and growing in my understanding of political economy and democracy. As I hope to have made apparent throughout this section; both the collapse of Kids Company as well as my induction into Digital Civics are events that were set against the backdrop of austerity. I either saw about me or continued to read about the continued effects of austerity in the UK: people not being able to eat (Dowler & Lambie-Mumford, 2015) and the subsequent rise of food-banks (Loopstra et al., 2015; Garthwaite, 2016; Garthwaite et al., 2015) 1; devastatingly widening inequality in already neglected areas (Greer Murphy, 2017); and the worsening health of the UK population (Stuckler et al., 2017). At the same time the climate crisis rages on (Chakrabarty, 2014; Dawson, 2010; Frank, 2009; Guerrero, 2018), and the disproportionately wealthy increase their share of our wealth with each new crisis (Woods, 2020; Kentish, 2017; Davies et al., 2017; Zucman, 2019). Through engaging with the works and analyses of political economy by writers such as Marx (Marx et al., 1974) and Lenin (Lenin, 1917) I could make sense of these systems and saw them not as disconnected, chaotic, results of a system gone awry; but the natural effects of capitalism.

The conditions of austerity and my subsequent readings of political economy coupled comfortably with my newfound academic interest in the Transparency and Accountability of charities and other ‘Third Sector’ organisations. I saw further evidence of the appropriateness of a focus on the third sector, as Marxist analyses of the sector (Livingstone, 2013; Bhai, 2005) gelled with the academic literature that the entire existence of these organisations was a result of the systemic failures of a political an economic mode that neglected or could not be trusted with key activities (Hansmann, 1980; Salamon, 1994). This solidified in my mind the notion of front-line charities as sites of struggle, and the appropriateness of following the thread this of working within charities in my research in order to lend my resources and (hopefully) insight into how to improve their efficacy or make their lives easier.

With the above in mind the aim of my research in this thesis is to explore how digital technologies may be designed with, within, and for charities (and related Third Sector organisations) in order to assist them with becoming more Transparent and Accountable. In doing this I hope that I may help them find ways to not only address their critics’ concerns over their work and spending, but better account for their impact on civic life in attending to the matters ignored by the state or exploited by the private sector.

This will, necessarily, cover an exploration of what it means to be transparent and accountable as or within such an organisation. Or more accurately, what it takes to do Transparency and Accountability. From this I wish to explore what the system and interface requirements are for supporting this work and making it more straightforward for a charity to demonstrate the appropriateness of its work and spending to its stakeholders, as well as civil society at large.

Owing to this research’s performance as part of the Digital Civics programme, and the fact that the on-the-ground work of charities is labour performed by members of the working class; I will also be reflecting on design practices in this space. Charities and their related organisations are an inherently civic space, and one with particular characteristics. Any act of designing technologies in, with, or for the workers in this space will need to attend to ensuring that the members of that setting have an adequate stake in design. Therefore, it is also an aim of this research to explore the performance of design work in this space both as it relates to designing tools for Transparency and Accountability, as well as how design may operate in charities as a matter of concern for Digital Civics work. This aim also aligns with a history of workplace studies within HCI and CSCW (Anderson, 1994); which have by their nature of forefronting work practice made matters of ‘accountability’ within the workplace a matter of study (Button & Sharrock, 1998). This traditional notion of accountability of work (or account-ability, as it is sometimes conceived) within ethnomethodological studies of work practice should be leveraged to frame the design of technologies which in turn provide the foundation for new forms of Transparent and Accountable practices beyond the immediate workplace and thus underpin the relationships between charities, their workers, and their stakeholders.

I now turn to forefronting the nature and contributions of this thesis and make explicit the research questions that, in answering, achieve the aims of purpose of this research. I also explicitly state and label the individual contributions that this thesis makes in answering these questions.

This section delineates the areas of work which this thesis sits at the intersection of and makes explicit the research questions that I am seeking to answer in this research in each case. I also highlight and explicitly label the contributions of the thesis in resulting from answering each question.

R1: How are the financial practices and Transparency obligations of a charity manifested in daily workplace practices?

As readers will discover in Chapter 2 there is a multitude of writing around the nature of Transparency and Accountability and how these interact in charities and the Third Sector. This does not account for how these obligations are present in the ground and experienced by the community surrounding organisations such as charities.

In order to begin designing for conceptual goals such as Transparency and Accountability there must be a study of how these concepts affect the daily work practices within organisations and settings where they’re important. Any systems designed to be used must consider the daily performance of workplace activity and how Accountability Work is organised as a result of this.

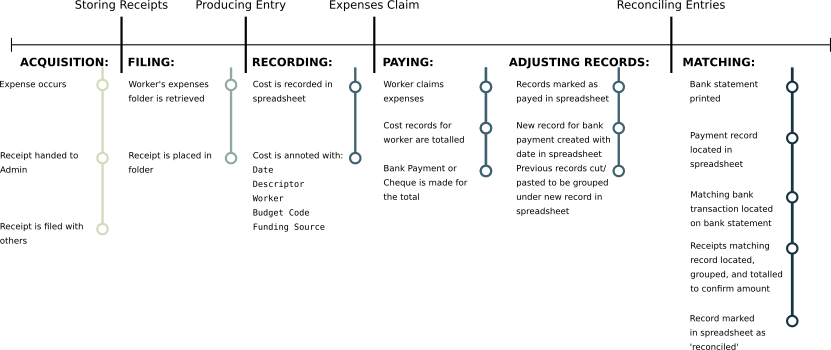

I address this question in Chapter 4 where I present my account of a field study of work practice inside a small charity. In this chapter I explicitly outline how Accountability Work is organised and performed, and put forward design recommendations based on this. In Chapter 6 I expand on this and illustrate how Accountability Work is underpinned by interactions with Accountable Objects.

Contributions

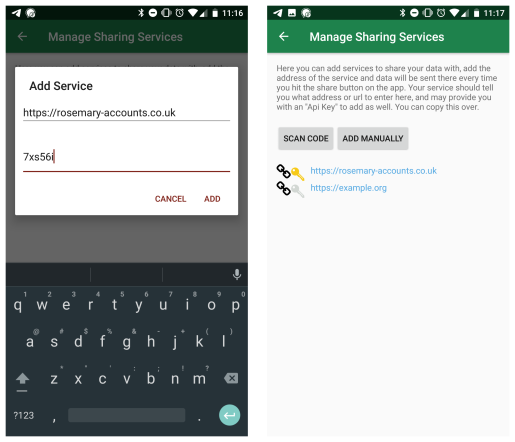

R2: How may data be structured to represent the work and financial life of a charity?

This thesis is concerned in part with the design and implementation of Open Data systems as a means to support Transparency and Accountability in charities. This requires attention on what is captured, how that is structured, and how well this represents the work of charities for achieving their aims in being Transparent and Accountable. In the realm of Open Data standards there has been work to model both government procurement (Open Contracting Partnership, 2021) and grants given to charitable organisations (360Giving, 2020a). My research seeks to add another piece to the puzzle around representing both work and financial practices on the ground in charities.

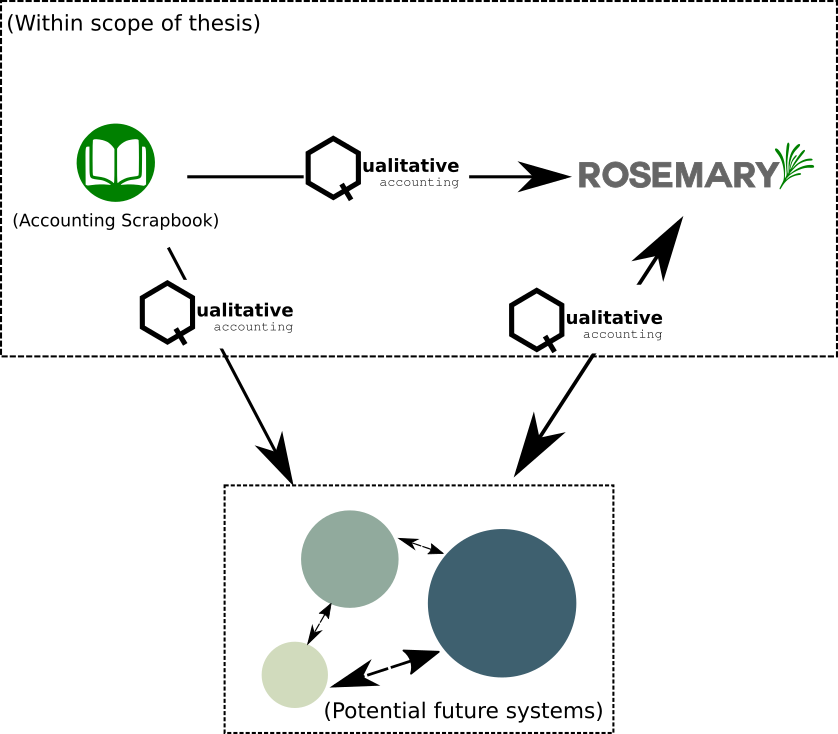

I address this question in two places. My first attempt at a model to capture and represent charity work and spending is documented in Chapter 5 where the first draft of the Qualitative Accounting data standard is designed with participants. The systems using the standard are then put to the test in Chapter 6 where I then further elaborate on these requirements based on lessons gathered from the field tests.

Contributions

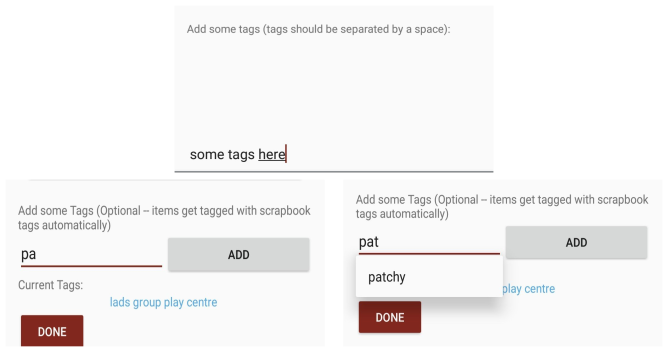

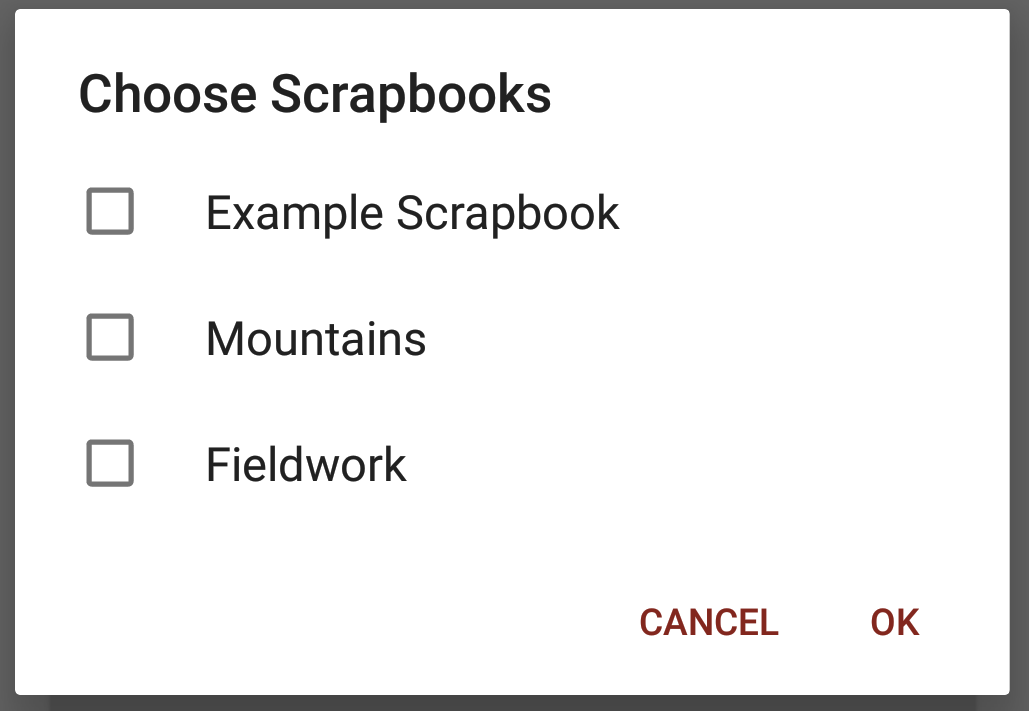

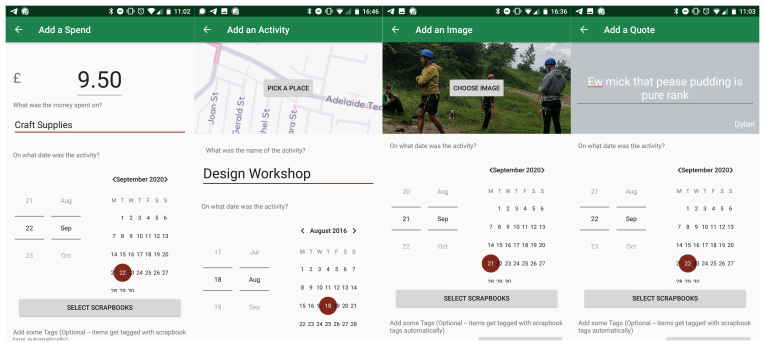

R3: What are the interface requirements for systems that interact with data concerning the work and financial life of a charity, such that it is simple to capture, curate, and make use of this data?

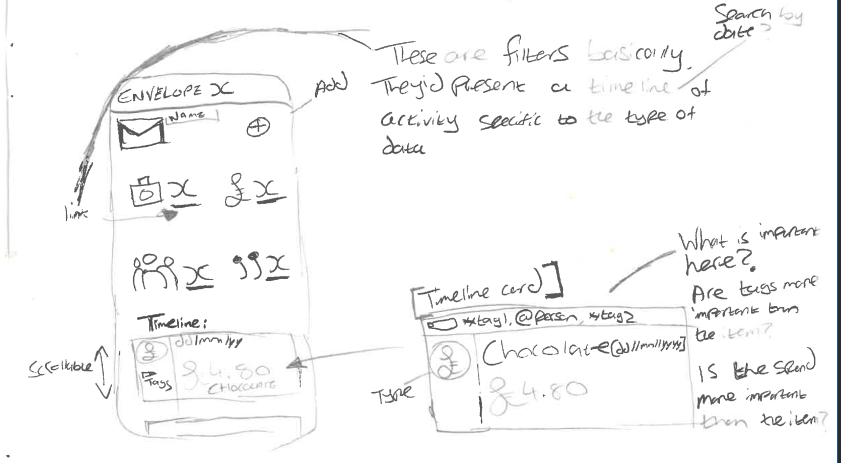

Building from R2, R3 explores the requirements for interfaces that support interactions with data as they pertain to charity work and spending. This question is situated in existing research into Human-Data Interaction (HDI) which has explored the use of data as a boundary object (Mortier et al., 2014) as well as interesting ways of engaging with personal data (Elsden & Kirk, 2014). If a model for representing charity work and spending is produced then it will require interfaces that allow people to capture this data, curate it, and engage with it in some way. I therefore contribute to this work by explicitly addressing the requirements of interfaces that interact with data with notions of Accountability and Transparency

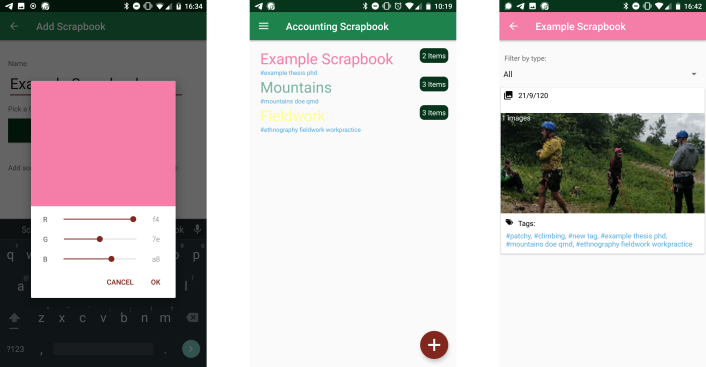

Similar to R2, I address this question in both Chapter 5 and Chapter-6. In the former I engage in a design process that results in several systems for collecting, curating, and presenting data whereas the latter chapter field tests these and I evaluate their effectiveness and forefront lessons learned from this.

Contributions

R4: How should design work be performed in civic organisations such as charities so that they can participate in design while operating with limited resources?

Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 each discuss this thesis as being performed within the context of the Digital Civics programme of work within HCI. Within Digital Civics, HCI, and related fields such as CSCW there is often reflections and research on the subject of design’s application within given settings e.g (Strohmayer et al., 2019) and (Bellini, Strohmayer, et al., 2019). The research performed in this thesis took place within small, front-line, charities in the UK; of which there are many. Lessons from this experience are also applicable to settings which experience similar struggles and where the relationship between the researcher/designer and the members of the setting is not necessarily clear-cut.

I begin addressing this in Chapter 5 where I discuss the challenges of performing design work in charities and conceptualise Vanguard Design as a model for dealing with these challenges. Chapter 7 continues this reflection based off of experience performing the research as a whole and contributes lessons for HCI and Digital Civics researchers seeking to engage with charities and other Third Sector organisations.

Contributions

This research has directly resulted in two publications to date, of which I am the primary author of both. The first of these is was “Accountable: Exploring the Inadequacies of Transparent Financial Practice in the Non-Profit Sector” (Marshall et al., 2016), published at SIGCHI in 2016. This was an output from the first year of the Digital Civics programme as a result of my MRes research project, which I then transformed into a publication with additional guidance from the other named authors. I have included it here because it motivates the work encapsulated in this thesis and I draw upon it early on for directing my early investigations.

The second of these is “Accountability Work: Examining the Values, Technologies and Work Practices that Facilitate Transparency in Charities” (Marshall et al., 2018), which represents a publication directly related to Chapter 4 of this thesis and thus R1, C1a, and C1b. Thus my contributions to this paper are of the research material, the analysis, and discussion as well as the writing of the paper. David S. Kirk provided feedback and suggested edits to the paper, while he other named authors provided light feedback on earlier versions

I have not yet made attempts to publish any further papers from this research but it is my intent to do so after this thesis has been appropriately examined and amended.

This thesis is structured to account for a research project that had the shape of a single long-term engagement or case study, which sought to design for and explore the implications of digital technologies in the realm of charity Transparency and Accountability. It starts with situating my research, outlining my methods and practices used to organise the research itself, provides empirical accounts of findings from fieldwork, design processes, and evaluations of technologies and presents a series of findings from each of these stages of the research. Finally I draw together these findings along with final reflections on the performance of the research in order to present contributions in the form of answers to the research questions outlined in section 1.3 of this thesis.

Chapter 2 provides the necessary background and academic literature necessary to engage with the remainder of the thesis. I first situate this research as being performed within the context of the Digital Civics programme of research (Olivier & Wright, 2015), particularly as it was conceived within Open Lab (Open Lab Newcastle University, 2021) at Newcastle University in the UK and elaborate on my place within that space. This chapter then introduces Third Sector Organisations (e.g. Charities, Non-Profits etc.) and explores their unique place within civic life, their importance to society as a whole, and their unique organisational challenges and pressures. Chapter 2 continues by exploring the challenge of Transparency and Accountability experienced by charities; and unpicks the dimensions of these terms so that this understanding may be applied to my research questions and analysis throughout the thesis. This chapter then explores existing research that explores the use of digital technologies in this space touching on notions of Open Data and Open Source technologies as a form of accountability, and interactions with data and finances that are supported through digital interfaces. Finally, I explicate the opportunities for research in this space at the intersection of digital technologies, the Third Sector, and Transparency and Accountability.

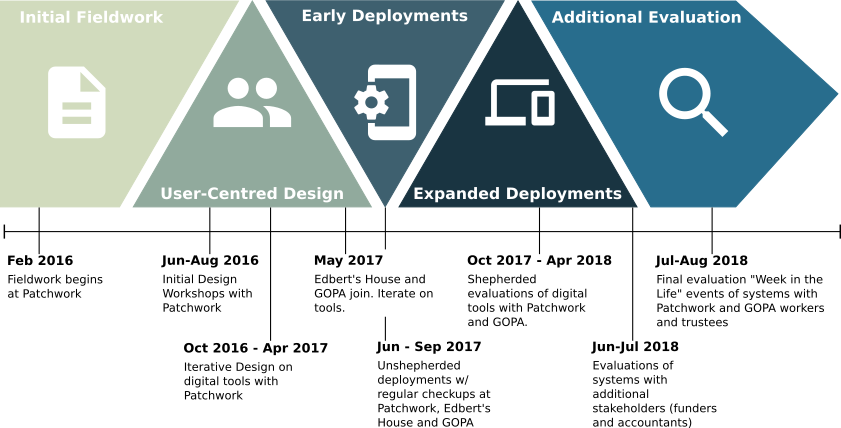

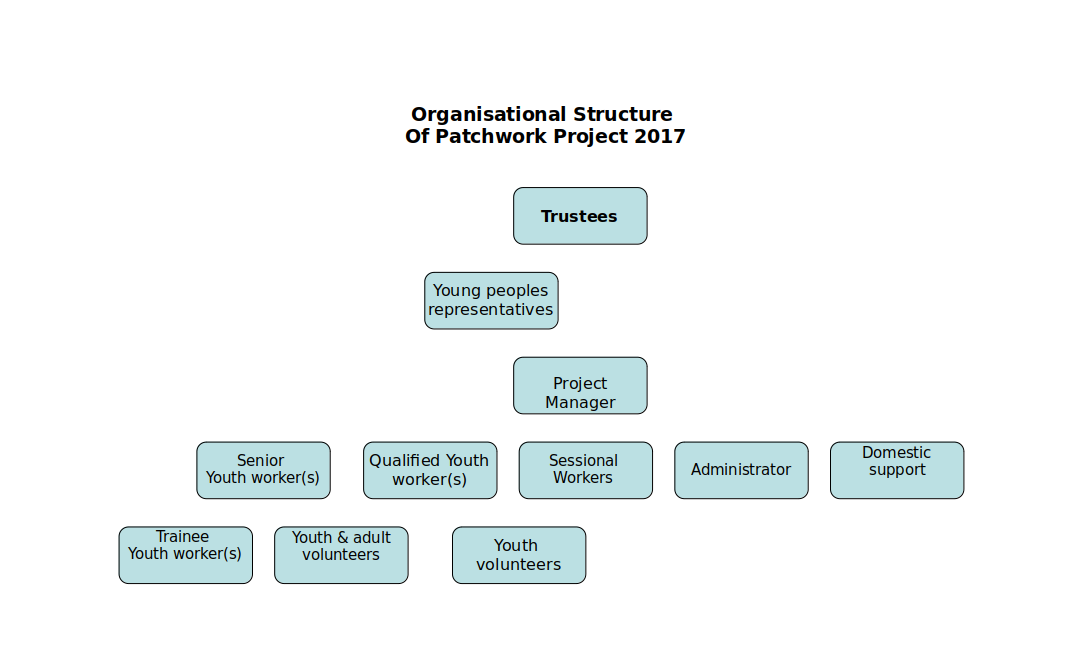

Chapter 3 outlines in detail the methodology and analytical heritage of the research that is presented in the thesis’ remaining chapters. I first outline this thesis as sitting within a tradition of Workplace studies and state how the setting and performance of the research fit within this tradition, as well as elaborate on how this framing is particularly appropriate for the research’s aims and objectives. Following this, I discuss the analytical orientations that were taken in this work: namely an approach inspired by Ethnomethodology to fieldwork and the study of work practice. I then present an overview and timeline of the research to situate it in the reader’s mind, and discuss the practical methods that were applied for the performance of fieldwork, design work, and the later evaluation of systems.

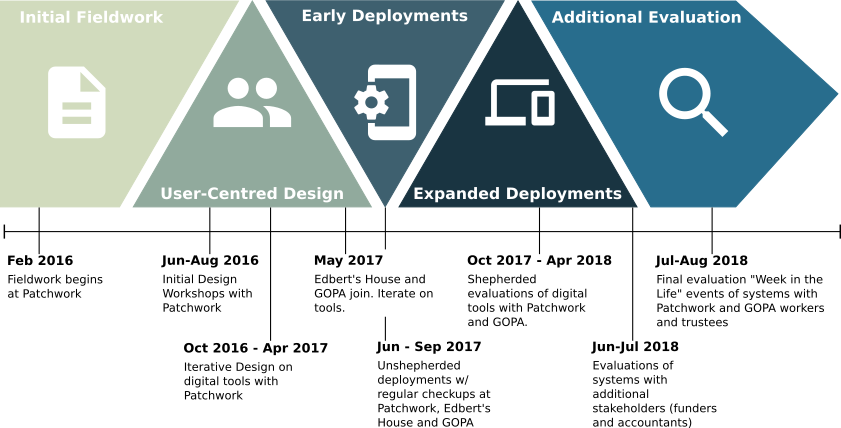

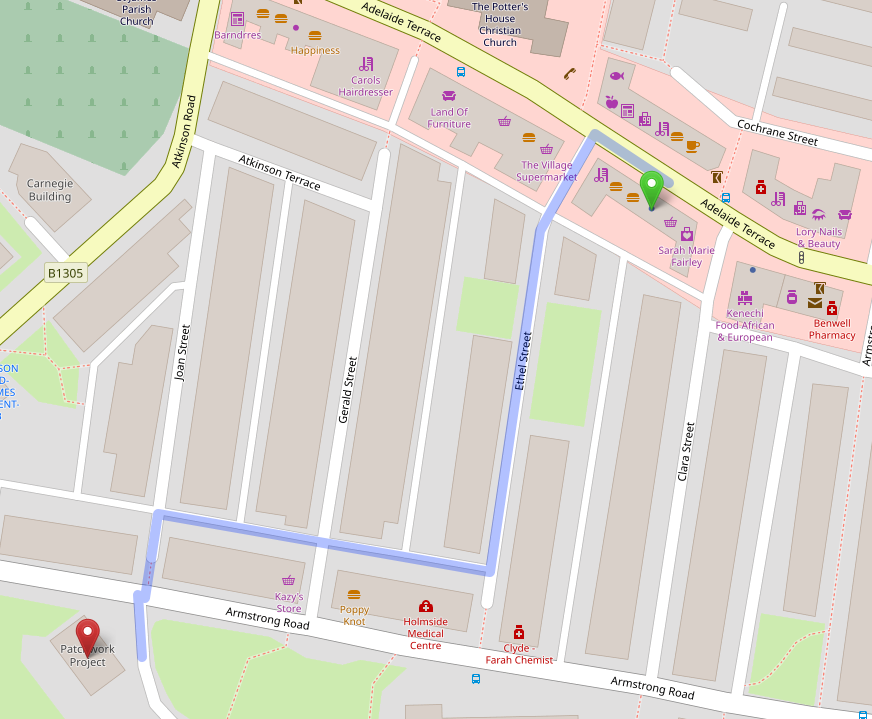

Chapter 4 presents the first empirical findings of the research as a study of work practice in a small charity. I first introduce the physical setting of The Patchwork Project (The Patchwork Project, 2021b) (Patchwork) as well as the staff who made up my collaborators during the bulk of this research. As part of my reporting on the setting and work practice I ensure readers of this thesis are aware of Patchwork’s broader aims, activities, and organisational structure in addition to their local setting within the West End Newcastle upon Tyne. The chapter then turns to reporting the work practices that make up Transparency and Accountability as it is manifested on-the-ground in the organisation. These are then used to derive early insights into the design requirements and characteristics of systems that operate in this space, describing the values that need to be embedded in their design as well as the architecture and characteristics they require to better enable Transparency and Accountability.

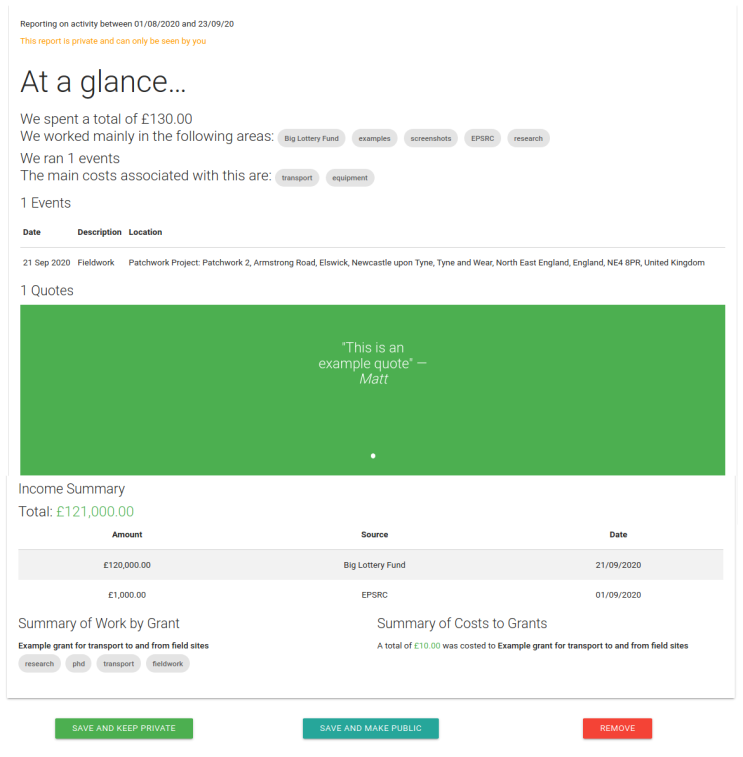

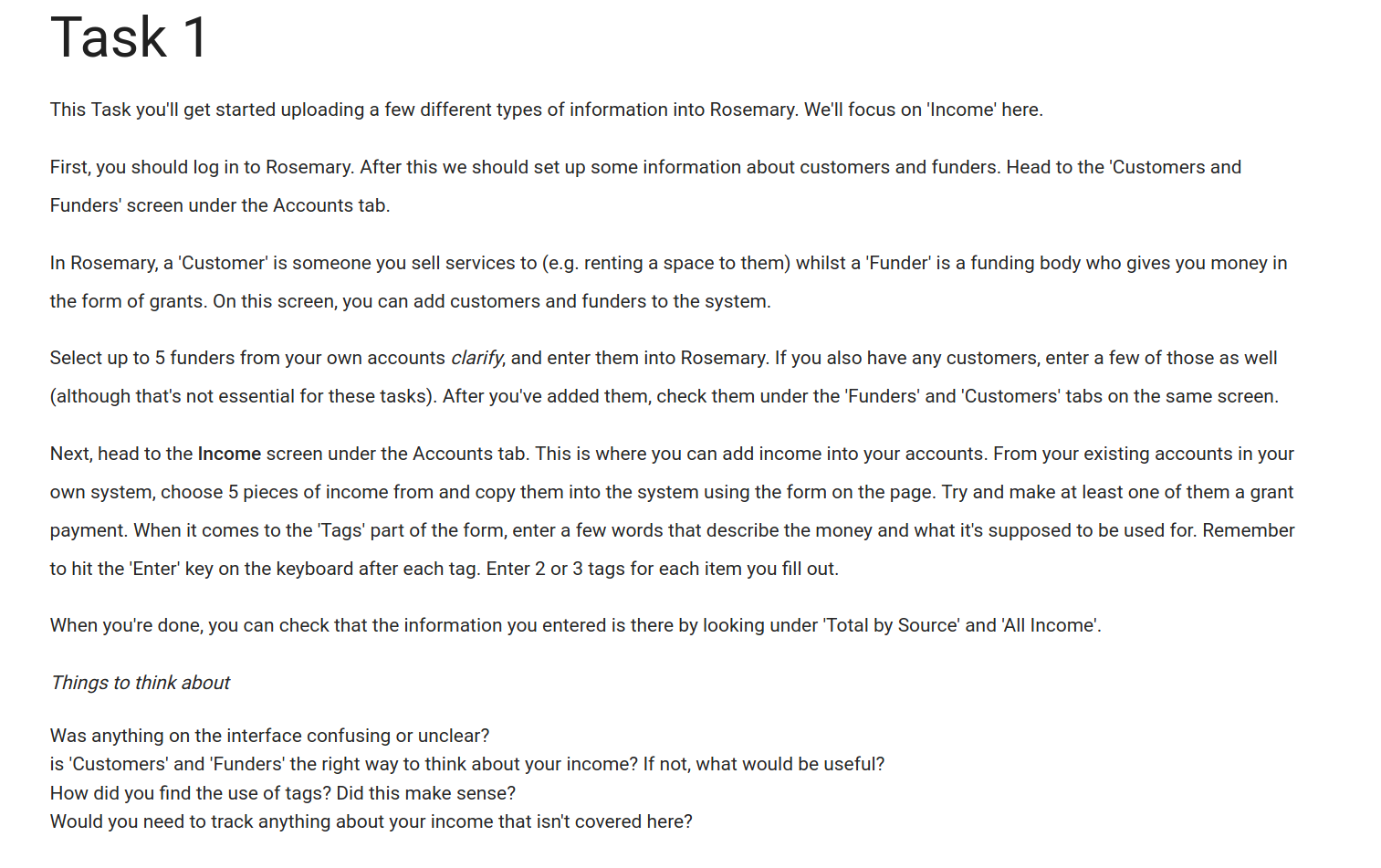

Chapter 5 provides a description the second empirical section of the research. This chapter covers the practice and output of the design work that immediately follows the fieldwork covered in the previous chapter. First I present an overview of the performance of the design work, going into detail about the activities that made up this phase of work such as the performance of design workshops, followed by a cycle of user-centred design. The chapter then goes into detail to convey the design and development of digital systems that were built to embody the lessons from Chapter 4 and address the challenges of the design space. I take care to present the design rationale for each major feature or design decision “in-situ” throughout this chapter so that it is clear where contributions of participants as well as insights from Chapter 4 were applied to the design. This chapter finishes with reflections on the performance of this design work; proffering lessons for the design of open data standards and infrastructure, as well as proposing a practical configuration of how to frame perform design work in a participatory and radical way in settings where participatory approaches may otherwise struggle to be applied.

Chapter 6 details an empirical study where evaluate the systems that were designed and built Chapter 5 are evaluated to determine their appropriateness and illuminate further design considerations. First I present an overview of how the evaluation was conducted across several stages in order to adapt to the material conditions of the participant organisations, as well as several new stakeholders that were approached for additional perspectives. I then present a series of grouped findings that illuminate the experiences and commentary of the participants who used the tools, and the stakeholders who reflected on the designs separately. Finally, I discuss future implications for system design in this space, demonstrating that data needs to strike a middle-ground between flexibility and openness and a need to tie actions to commitments as well as the implications for the interfaces that make use of this data, and how different forms of Transparency may benefit from this.

Chapter 7 accounts for all of the work collected in the previous chapters of this thesis. First I account for each of the research questions that were outlined in Chapter 1 and answer each of them using examples from the research. In doing so I demonstrate a contribution of knowledge in each case. Following this I then discuss the broader implications of the research in this thesis as situated within both the Digital Civics programme and within the context of Open Data, Transparency, and Charities. I draw on the issues faced by both myself and my contemporaries at Open Lab and provide a critique of Digital Civics’ initial framing and motivations. In doing so I highlight ways in which the performance of HCI research within civic spaces, especially the Third Sector, may contribute more impactfully to civic life.

Chapter 8 concludes the thesis. In this chapter I summarise research as well as and insights that have been contributed throughout the rest of the thesis. I use these contributions to frame the importance of doing additional work and suggest the immediate concerns that should be forefronted in successive research.

This chapter discusses the background and literature of the various fields that inform this research. Given the interdisciplinary history of HCI research, and the socio-economic domain of non-profit enterprise, it should come of no surprise that this results in a rich and diverse nexus of perspectives which needs to be accounted for.

The chapter begins with grounding this focus within the space of Digital Civics before beginning an exploration of Charities and other forms of Third-Sector and Community Organisations in order to reach a workable definition of the term and ground the importance of these organisations to society as well as the challenges they face. Having reviewed these challenges the chapter then focuses on the Transparency and Accountability of these organisations and reviews the often ambiguous use of these terms and the challenges of producing Transparency and Accountability within an organisation. Next, the chapter explores the use of digital technologies as means to address these challenges through considering intersecting strands of research in interacting with data and finances through digital technologies.

Finally, the chapter ends by discussing the opportunities for research in this space that the thesis will explore in following chapters.

The research in this PhD thesis was performed alongside others and was framed as part of the Digital Civics program of work. As a term, Digital Civics is applied to a set of work addressing the roles, power, and potential of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) to explore, learn from, and shape civic life through digital technologies. The term Digital Civics encompasses a varied set of research with themes of: trust; civic participation; localism; engagement with civil society organisations; and citizen commissioning (among others). I elaborate on these below, but it is not the remit of this thesis to provide a single canonical definition of Digital Civics. I do, however, wish to explore the term through reviewing work that was performed either explicitly under a Digital Civics banner or is otherwise held up as an example of the space2.

It is my personal opinion that a definition of the term Digital Civics and its relationship to the work it represents is, complex and bi-directional. By this I mean that, by merely existing as a term, Digital Civics shapes and is in turn shaped by the work to which the term is applied. Therefore in lieu of a single, unchanging, definition with which I may boldly and confidently declare my work an example of, I instead wish to offer a short review of the space as I experienced it. First I consider broadly the use of the term Digital Civics before focusing on examples of research in the space that intersect or run parallel to my concerns – namely work that occurs at a local level and then specifically that which occurs within or is focused on charities and community organisations. Through this I hope both to establish this thesis as a work of Digital Civics, grounding its motivation and concerns, and open the space of Digital Civics itself to contributions from my research.

The term Digital Civics is not specific to a single stream of work coming out of Newcastle University but has been used internationally by researchers in the US, primarily in the Georgia Institute of Technology. Corbett and LeDantec explore the role of trust in technology, communities, and civic participation (Corbett & Le Dantec, 2018b, 2018a; Corbett & Le Dantec, 2019). Through collaborations with a municipal government in the US, Corbett and LeDantec explore how trust is operationalised in these settings through Trust Work and subsequently how trust may be designed for (Corbett & Le Dantec, 2018a). Further to this, they also discuss how technology may be used to design community engagement; asking the question whether Digital Civics interventions should be responding to user need or whether they should be designing for behaviour that is expected of the governance process (Corbett & Le Dantec, 2018b). Dickinson et al writes of the use of “civic technology” as a tool to support strengthen community assets, and how design may consider an asset-based approach to support building relationships between citizens and their governments; contrasting the “data-driven” agenda that conceptualises these interactions as purely transactional (Dickinson et al., 2019). In this vein Møller et al investigate citizen experiences of a social welfare system and highlight how the datafication of services shapes the experience of the system where data about a citizen is increasingly hard to access and contest by the very citizens it describes (Holten Møller et al., 2019). In the arena of public housing, Kozubaev et al demonstrate how smart home technology use in these spaces may be appropriated by residents as a form of self-organisation through tracking practices but demonstrates the blurring of the private and public that can arise as a result (Kozubaev et al., 2019), while Rumsey and LeDantec demonstrate that smart tracking technologies are now beginning to enter spaces such as the emergency services (Rumsey & Le Dantec, 2019).

The stream of work I am more familiar with is that coming out of Newcastle University where I was conducted my research as part of the centre for doctoral training in digital civics (Olivier & Wright, 2015). As noted by Olivier and Wright , the initial framing was to explore a more the ways digital technologies may support a more relational model of service delivery between local government and civil society. The early examples of these work (pre-dating the start of the doctoral training centre) are exemplified in projects such as PosterVote (Vlachokyriakos et al., 2014), Bootlegger (Schofield et al., 2015), Feed Finder (Balaam et al., 2015), and the subsequent App Movement platform (Garbett et al., 2016). All of these projects share as a concern the community production of value as well as acts of commissioning which are mediated or enabled through a digital platform.

The theme of platforms and commissioning influenced the “flavour” of some of the later work that was performed under the Digital Civics banner at Newcastle. Dow et al explore a platform for care organisations to commission feedback (Dow et al., 2016) while Johnson et al explored platforms for community decision making (Johnson et al., 2016). The value of this work both in its contributions to framing Digital Civics as well as their contributions to HCI and Design can not go under-stated, but Digital Civics expanded its reach to consider other forms of both local engagement and internationalist areas of work. The Parklearn project engaged in field studies to understand the role of technology in community-lead learning (Richardson et al., 2017, 2018) and WhatFutures considered the role of utilising existing platforms to design large-scale engagements rather than designing a new, bespoke, platform (Lambton-Howard et al., 2019). Prost et al consider technology’s role in Food Democracy (Prost et al., 2018, 2019) where Talk et al discuss the role of HCI and design in working within the contexts of a humanitarian crisis (Talhouk et al., 2018; Talhouk, Balaam, et al., 2019)

This is by far an exhaustive account of Digital Civics research but I hope serves simply to illustrate the breadth of concerns that fall under this umbrella. These researchers worked in a very diverse set of spaces in a diverse set of ways. Critically, they not only explored technology and design’s role in these spaces but drew insight from their engagements that helped to shape the way Digital Civics and HCI research at large is performed. Taking this into account, I feel that Digital Civics is less of a focus than a nexus of research and one that my work sits within. Where some work takes on a more explicitly internationalist set of concerns (e.g. (Talhouk et al., 2018; Lambton-Howard et al., 2019)), my work sits more closely in the sphere of local-scale engagements; particularly around charities and non-profit organisations. This review now turns to briefly highlight some work more closely aligned to mine in terms of both local engagements and charities.

A distinct theme within Digital Civics research as it was performed in Newcastle was that of localism – that is the local engagement of citizens, local politics, and other local civic matters. This took several forms within Digital Civics which I will briefly highlight examples of here.

The work of Johnson et al was mentioned briefly earlier in this section, where I cited it as an example of a technology that investigated community decision making (Johnson et al., 2016). Johnson et al’s work also contributes considerations into the role of the researcher as agent in civic technology deployments, and how the social capital of the researcher was important at a various points during the research (Johnson et al., 2016). Johnson et al expand their work around communities to explore and capture reflections on “deliberative talk” in consultative processes, and raise the implications of data systems’ supposed impartiality in supporting local deliberation (Johnson et al., 2017). Puussaar et al similarly examines how groups may make sense and share data (Puussaar et al., 2017), but also, working with Johnson, Johnson a critique of how Open Data may be made more useful for civic advocacy through deployment of a data platform that supports citizen interrogation, and (Puussaar et al., 2018). Additionally, Johnson et al further explore the role of data technologies in policy making and contribute considerations for building democratic and epistemic capacity through data as a participatory process (Johnson et al., 2018).

Richardson et al also consider local space and engagement in Digital Civics. They highlight how mobile technologies (through the Parklearn platform) may be used for civic M-learning, but also provide implications for harnessing existing social and civic infrastructures within design (Richardson et al., 2017). Richardson et al then expand on this with field studies of Parklearn to complement classroom activities and present discussion of how these deployments lead to participants having increased senses of ownership of their civic spaces (Richardson et al., 2018). Wilson et al have similarly feature community ownership discussion through their work with Change Explorer; a platform which leveraged smart watches to promote citizen engagement in planning processes which was shown to support participants in thinking critically about the areas they inhabit (Wilson et al., 2017).

The civic and often local nature of charities and similar organisations lends them to alignment with the goals and areas of Digital Civics research. Many of my colleagues have been been engaged in collaborations with charities in their work, often as the spaces they operate in are also the concern of charities and charitable work.

Dow et al, explored the role of feedback technologies (ThoughtCloud, mentioned above) in care organisations that were charities (Dow et al., 2016). Throughout an extended engagement with these partners Dow not only had insights pertaining to the design of feedback technologies throughout the project (Dow et al., 2017), but also at later stages of the research drew important reflections on the material concerns of working within the space and the contradictions between grassroots desire for change and institutional rigidity (Dow et al., 2018). A similar set of extended engagements is that of Bellini et al, working within charities most notably in the arena of domestic violence perpetrator programmes. This extended collaboration has involved delivering such a programme alongside Bellini’s collaborators as part of her research, and therefore has incredibly important lessons to draw on ensuring design work does not undermine the trust of the service-providers-cum-collaborators (Bellini, Strohmayer, et al., 2019; Bellini, Rainey, et al., 2019)

Another good example of Digital Civics work within charities is the work of Strohmayer (Strohmayer, 2021); which also involves prolonged engagements utilising methods deriving from feminist and social justice methodologies. The first of these examples was through a partnership with the UK organisation National Ugly Mugs (NUM) (National Ugly Mugs, 2021), and draws attention to the potential of carefully considered technologies and design to feed into the critical work of sex work support services; even through the use of technologies most HCI researcher may consider mundane (Strohmayer et al., 2017). A later collaboration with a Canadian non-profit expands this work to an international space and highlights the pressing need for contextualisation in technology design and to cater to multiple formats (Strohmayer et al., 2019). In doing this, Strohmayer et al also bring to the fore the need to understand contexts not from the position of researchers and designers but from the position one is designing from. An important consideration for any piece of work calling itself Digital Civics and one that exemplifies the dialectical nature of the term.

Finally, it should be acknowledged that this practice, space, or context of working within, alongside, or through charities and community organisations has been explored more explicitly through a previous collaboration between myself and Strohmayer at Newcastle but also international colleagues Verma and Bopp, as well as McNaney who was operating out of Lancaster at the time (Strohmayer et al., 2018). Although reflections on the performance of HCI and Design research within the “Third Sector” is still emerging as a scope of study, this work should be acknowledged as one that is both born of and contributes to Digital Civics research.

This section has considered the positioning, concerns, and shape of Digital Civics research as a field as well as individual work within it. I hope both to have showcased the variety of approaches and foci of work that is performed under the banner of Digital Civics and to have demonstrated that there exists a convergence of engagements that primarily centre local engagements as well as engagements with civic organisations such as charities and other forms of non-profit.

With this established, it may be demonstrated that my work sits within this programme of research and thus exists as a work of Digital Civics. This review now turns to exploring some the background of my more direct concerns around Charities and their role in civic life to ground the focus of my research in this space.

This section explores Charities and Non-Profit Organisations (NPOs); how they are defined, and what role they play in society. This is done for two reasons: firstly, to explore the ecosystems, landscapes, and settings within which these organisations operate so that the research is effective; and secondly, to ground the work’s relevance as playing a part in the everyday activities of the world.

Given that this thesis revolves around the design of digital technologies to support the work of charities, it is important to set forward a definition of a charity what its work may be. However, defining what constitutes a charity can be problematic because it is a specific form of organisation that belongs to an entire sector or family of organisations which have historically resisted definition (Salamon & Anheier, 1992b; Morris, 2000). This is largely due to the sheer diversity of both the organisations themselves as well as the legal and social frameworks in which they operate (Salamon & Anheier, 1992b). Even choosing which term to use is problematic not only because any given term can emphasise particular traits of organisations or exclude some organisations entirely, but choosing what term to use will give any discussion a particular national flavour. For example, the term ‘Charity Sector’ is often used in the UK whereas framing this discussion using the term of ‘Non-Profit Organisations’ (NPOs) makes it feel distinctly relevant to the USA (Frumkin, 2009). However, as noted, these organisations all share a genealogy, which means utilising literature that in turn uses a variety of terms to describe this group of organisations. A working definition of ‘a charity’ will be outlined at the end of this section.

Charities are a form of Non-Profit Organisation (NPO) which operate within what is often known as the “Third Sector” of the economy; emphasising their separation for public or state-owned operations as well as private for-profit enterprise (Salamon & Anheier, 1992b). The term ‘Third Sector’, however, is often used interchangeably with others such as “Voluntary Sector”, “Independent Sector”, “Charitable Sector”, or many others. Salamon and Anheier claim that this abundance of definitions often poses a problem, as each term emphasises a particular characteristic of these organisations whilst downplaying others – which can be misleading when attempting to describe them (Salamon & Anheier, 1992b). An example of this would be how the term “Voluntary Sector” emphasises the contributions of volunteers in the operation of the organisations, at the expense of organisations or activities that are performed by paid employees. Frumkin prefers the term “Non-Profit and Voluntary Sector” for this reason (Frumkin, 2009).

This diversity of organisations within the “Third Sector” means that a general definition is difficult to generate, however Salamon and Anheier go some way to provide one based off of the structural or operational characteristics of the organisations; which would therefore allow their definition to cater for the sector’s diversity of legal structures, funding mechanisms, and function. Their definition identifies five base characteristics common to the organisations (they use the term NPOs). These organisations are: “Formal”, having been constituted or institutionalised legally to some extent; “Private”, meaning they are institutionally separate from government; “Non-Profit distributing”, where any profits generated by activities are reinvested directly into the ‘basic mission of the agency’ instead of being distributed to owners or directors; “Self-governing”, with their own internal protocols or procedures as opposed to being controlled directly by external entities; and “Voluntary”, where the organisation’s activities or management involves a meaningful degree of voluntary participation (Salamon & Anheier, 1992b).

Frumkin gives three characteristics of these organisations which align with Salamon and Anheier’s framework. The organisations: do not coerce participation (ie they do not have a monopoly and interacting with them is optional); their profits are not given to stakeholders; and they lack clear lines of ownership and Accountability (Frumkin, 2009). These definitions are not without issue, as they notably exclude various quasi-commercial entities such as those found in the UK – ie Building Societies and Cooperatives.

It is the exclusion of such entities that presents an issue for achieving a working definition. Lohmann calls for a more expansive view of the “Nonprofit Organisation” since definitions often account only for those legally bound by particular legislation and that if academics work only within these confines then they are limited in their attention (Lohmann, 2007). Lohmann also takes issue with the term “Third Sector” as it often is not presented in context of what it is a sector of. Lohmann argues that the organisations generally included in definitions of the “Third Sector” are actually simply a part of a broader grouping termed the “Social Economy” which would include NPOs and Charities but also others such as cooperatives and member organisations (Lohmann, 2007). Moualert and Ailenei elaborate that the term “Social Economy” is tied with notions of economic redistribution and reciprocity, and argue that a “one-for-all” definition is not useful to produce, as the organisations within the Social Economy are driven by local contexts (Moulaert & Ailenei, 2005). They put forward that the Social Economy as a practice, as well as the institutions that make it up, are linked to periods of crisis – and that the Social Economy is a method to respond to the alienation and dissatisfaction of people’s needs by the For-Profit and State sectors at any given time (Moulaert & Ailenei, 2005). Monzon and Chaves go into detail about defining the characteristics of organisations that make up the Social Economy, largely echoing the definitions for the US-centric “NPOs” discussed earlier (Monzon & Chaves, 2008). In addition to this is their elaboration that “[the organisations] pursue an activity in its own right, to meet the needs of persons, households, or families … [They] are said to be organisations of people, not of capital … They work with capital and other non-monetary resources but not for capital.” This indicates that the unifying characteristic of these organisations is their concern for people, and begins to define them based on what they are rather than the via negativa of “Third Sector” (Monzon & Chaves, 2008).

In the UK, the term ‘Charity’ is protected and has a specific definition enshrined in law. According to the Charities Act 2011, a Charity is an organisation that is “established for charitable purposes only”, where the Act then later defines a list of charitable purposes to ensure that the organisation is acting for the public benefit (UK Government, 2011). These cover a wide variety of purposes and such as “the prevention or relief of poverty” and “the advancement of citizenship or community development”. Whilst this mirrors the Monzon and Chaves assertion that organisations pursue activity to “meet the needs of persons…”, it is the opinion of this thesis that enshrinement in law is not necessary treat an organisation as a charity for the purposes of research. This is so that any outcomes of the research can be applied to international contexts – where different legal definitions of the word “Charity” may exist. To that end, our definition of a charity going forward takes the common threads discussed in this section that Charities are: not-for-profit organisations that are legally distinct from government; are set up towards a charitable purpose (regardless of whether that purpose is enshrined in law); and that a citizen’s interactions with the organisation are voluntary. This definition will allow the remainder of this chapter (and subsequent research) to consider multiple types of legal entity within the UK and internationally to explore this space.

Charities are seemingly inherently valued by most individuals in civil society. The social motivations behind Charities and the wide variety of activities in which they involve themselves, as well as the manner of their involvement often means that the health of Charities, and the Social Economy more broadly, are often used as barometers for the health of civic society (Moulaert & Ailenei, 2005). I therefore wish to to explore the importance of Charities to society in order to understand better the world in which they operate.

Hannsman writes on the role of Charities that they often emerge from a “contract failure” of the market to police the producers of services, and that it is very rare to find Charities operating in industrial sectors (Hansmann, 1980). According to Hansmann, economic theory dictates that the failure is in accordance with consumers (as a group rather than individuals) to do one of the following: accurately compare providers; reach agreement as to the price and quality of services to be exchanged; and to assess the compliance of the organisation to their part of the deal, obtaining redress if the organisation is seen to have not complied. Charities emerge, therefore, when this process has failed to regulate For-Profit actors in any given economic activity: “The reason is simply that contributors [to a for-profit business] would have little or no assurance that their payments … were actually needed to pay for the service they received” (Hansmann, 1980, p.850). As noted, it is uncommon to find Charities operating in industrial sectors, and as such the services offered by these organisations can often be those that involve a separation between the purchaser of a service and the eventual recipient; e.g. the purchase and transport of food aid overseas. The inability of Charities to distribute profits to shareholders thus removes the incentive and power of organisations to reduce direct spend on the service; reassuring the purchaser that their money is not for the direct profit of shareholders (Hansmann, 1980).

Salamon writes that Charities “deliver human services, promote grass-roots economic development, prevent environmental degradation, protect civil rights, and pursue a thousand other objectives formerly unattended or left to the state” (Salamon, 1994, p.109). This insight reinforces Hansmann’s view that the activities of these organisations are concerned primarily with provision of services unattended to by For-Profit sectors. Salamon’s statement also implies the presence of State actors in a given activity and that State-provided services would mean that there is no requirement for a Charity actor if the needs of the people were being met. Frumkin argues that a core part of the Third Sector and Social Economy (which would include this thesis’ definition of ‘Charity’) is that it is responsive to demand; specifically the demands of a public who have unmet needs (Frumkin, 2009). Not only does Frumkin’s argument add weight to both Hannsman and Salamon’s admonition that the For-Profit sector is either unconcerned or untrusted with particular activities, but also that the State is either an absentee actor or that the service provided is unsatisfactory in meeting the needs of the public.

The nature and scope of activities in which Charities are involved are incredibly diverse. Salamon and Anheir outline a classification system, the International Classification of Nonprofit Organisations (ICNPO), that divides and classifies organisations into 12 groups based on economic activity, with an additional 24 sub-groups (Salamon & Anheier, 1992a). Whilst this classification system generally only provides high-level descriptors of organisations, lacking detail on the nature of how activities are performed pragmatically on-the-ground, they offer a starting point from which to begin to understand the far-reaching and diverse nature of the sector’s activities. Examples range from “Nursing Homes” and “Mental Health and Crisis intervention”, to “Housing” and “Culture and Arts”.

The activities undertaken by Charities are also important to society because they are generally understood to produce and sustain Social Capital (King, 2004; Wang & Graddy, 2008; Swanson, 2013). Generally, Social Capital is the term used to refer resources and access to those resources as permitted by one’s social network (Field, 2003). Putnam defined Social Capital as “features of social organisation, such as trust, norms, and networks, that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated actions” (Putnam et al., 1994, p.167). The ‘resources’ in Social Capital may be physical resources (ie tools) or more intangible types of resource such as possessing a skill or qualities that are valuable to society.

The amount of Social Capital an individual (or group) possess can have substantial effects on their day-to-day lives in a variety of areas. Field discusses how an increased amount of Social Capital has effects on personal health and happiness, as well as the educational prospects of one’s children, and the amount of “anti-social” behaviour present in their communities (Field, 2003). Conversely, low amounts of Social Capital within communities can manifest as poor socio-economic conditions such as higher crime rates and low employment. Field writes about two flavours of Social Capital: ‘bonding capital’, which strengthens bonds between sociologically similar groups such as close friends and family; and ‘bridging capital’ which connects members to existing networks originally distinct to their own (Field, 2003). Bourdieu discusses how the bonding capital can be a means to denote or sustain privilege in society (ie the Old Boys’ Clubs) (Nash, 1990), and Putnam similarly states that whilst bonding capital can get one by, bridging capital is required to ‘get ahead’ (Putnam et al., 1994; Woolcock, 1998).

With this in mind, it becomes easier to understand how the activities undertaken by charities are linked to the health of society. As discussed, their activities are generally grassroots in nature and as such can involve producing bonding capital between actors who are their beneficiaries in addition to providing opportunities for developing bridging capital that people would otherwise not be presented with. It is also worth noting that Field discusses that there requires an investment in more than just network building in order for society to benefit from Social Capital – the individuals who form the network must also learn skills in order to benefit each other (Field, 2003). This is also an activity that is generally attended to by charities; organisations within this sector often concern themselves with benefiting others in the form of ‘skills development’ of either specialist forms or of a more generalised and transferable nature that were denied to them because of their existing sociological standing (Anheier et al., 1995).

Like any organisation, charities experience a set of pressures dependent on their circumstances, with the heterogeneity of the sector meaning that each individual organisation will be subject to unique pressures. Generally, however, it is understood that there are a range of pressures that operate on Charities across the board.

As of writing, in the UK we have experienced nearly a decade of austerity politics which has resulted in significant reduction of funding to national services as well as Local Government Organisations (known as Councils) (Reeves et al., 2013; Lowndes & Gardner, 2016). The result of this is that Charities are having to supply people with the services that they require either independently providing services that were once provided by the Councils, or working as a contracted official supplier of a service once provided “in-house” . At the same time, the change in national leadership associated with the austerity agenda has lead to uncertainty in UK charities securing adequate funding to meet their needs as government grants are reduced or disappear entirely .

In response to this shifting environment, many Charities organisations are switching their operational model to that of a Social Enterprise (SE) or Social Entrepreneurship in general (Borzaga & Defourny, 2004). SEs are, yet again, a diverse set of organisations — but one that specifically combines business-like elements, activities and structures from the For-Profit sector and applies them to activities that are intended for social betterment and benefit to society; much like traditional charity organisations (Defourny & Nyssens, 2008; Doherty et al., 2006). Dart broadly describes Social Enterprise as “significantly influenced by business thinking and by a primary focus on results and outcomes for client groups and communities” (Dart, 2004, p.413), and Dees states that Social Enterprise combines the passion of a social mission with an image of business-like discipline (Dees et al., 1998). In practice, this often includes activities and practices that include revenue-source diversification, fee-for-service programs, and partnerships with the private sector . Defourny and Nyssens describe the rise of SEs across the world, and that the UK has used the SE ‘brand’ within policy documents for years, and give as part of the working definition that the organisations profits are “principally reinvested for [a social mission] in the business or community, rather than being driven by the need to maximise profit for shareholders and owners” (Defourny & Nyssens, 2008, p.6). This definition shares similarities to that for Charities discussed earlier in the review – however distinctly does not include the requirement that profits cannot be distributed to shareholders, only that they principally are used primarily towards an organisation’s social mission.

SEs are often cited as a solution to the issues being experienced by Charities, but they are not without criticism. Eikenberry writes that organisations adopting a social enterprise model actually poses a threat to civil society (Eikenberry & Kluver, 2004). She argues that change in model leads to a focus on the bottom line and overhead expenditures, and exposes them to market forces that they would otherwise be sheltered from. Aside from the effects on the organisation itself, this exposure means organisations can often adopt “market values” and “entrepreneurial attitudes” which means that the change in their operational model is detrimental to society (Eikenberry & Kluver, 2004). Dart elaborates that SEs differ from traditional NPOs as they generally blur boundaries between nonprofit and for-profit activities, and even enact “hybrid” activities (Dart, 2004). This could include activities such as engaging with marketing contracts as opposed to accepting donations, as well as behaviour such as cutting services that are not deemed to be cost-effective. Whilst there are large implications for organisations accepting funding from for-profit industries, a major implication of changing operational model is that the shift of effort from effective service delivery to financial strategy impacts negatively on the Social Capital that is generated (Eikenberry & Kluver, 2004). This is through less emphasis on building relationships with stakeholders (previously an essential survival strategy) as service users become framed as consumers, and through market pressures diverting resources towards skills such as project management and away from activities that build Social Capital. Doherty et al. echo this in their description of Social Enterprises, distinguishing them from traditional models of Charities by stating that the latter are “more likely to remain dependent on gifts and grants rather than developing true paying customers” (Doherty et al., 2006, p.362). Eikenberry’s concerns are manifested here, as the service user or “beneficiary” of an organisation becomes reframed as a “customer” due to the influence of market forces.

Social Capital plays a significant role in the success of a Charity organisation. As actors within social networks themselves, these organisations need to make use of Social Capital in addition to their pivotal role in producing and sustaining it for others. King writes that Charities were formed using Social Capital and part of their role is to “sustain and broaden” it in order to provide opportunities and make the mundane operation of an organisation smoother (King, 2004). She writes that those in leadership positions within an organisation draw upon techniques such as networking and skills development in order to allow the organisation to perform its work and meet its goals – calling Charities (she uses the term nonprofits) “the epitome of Social Capital in action” as the organisations can not only utilise but spread their Social Capital to others (King, 2004, p.483). Swanson shares these sentiments and explicates that strategic engagement of an organisation’s Social Capital should be a central tenant in its management and leadership, Fredette and Bradshaw echo this and discuss how bonding capital established between those in leadership roles allows them to collectively mobilise through the sharing of information and the building of trust (Swanson, 2013; Fredette & Bradshaw, 2012).

Trust is inextricably tied to Social Capital, as Field discusses that a network with high trust levels operates more efficiently than one with comparably lower levels of trust (Field, 2003). This means that in order for a Charity actor to achieve its goals more effectively, it must be trusted. Whilst it is important to note that there is some disagreement as to the exact nature of Trust within Social Capital ie whether Trust is a product or instigator of Social Capital; it remains that high levels of Trust allows an organisation to operate more effectively, and continue the cycle of production and sustenance of Social Capital for their stakeholders (Field, 2003). Schneier writes on Trust that it is essential for society at large to function (e.g. we trust in our currency, we trust in our qualifications etc.), although on-the-ground Trust plays a key role in accessing resources in the social network, since a transaction between two trusting actors is less expensive (both in terms of emotional labour and financial capital) to facilitate than a similar transaction between two actors lacking trust (Schneier, 2012). Trust, therefore, is an important factor for Charities in the performance of their work as lack of Trust will impede an organisation as much as high Trust will aid them.

It can be said, then, that since Charities perform work that is important to society and needs to be performed, and that since high levels of Trust allows them to operate more effectively; that it is important to society that we trust our Charities organisations to perform the work that they do. However, recent media coverage (at least in the UK) has often portrayed Charities organisations as being irresponsible with funding, ineffective in achieving the outcomes they purport to desire, and in some cases unaccountable for their actions (Benedictus, 2015; Beresford, 2015; Bright, 2015; Laville et al., 2015; Letters, 2016; Smedley, 2015). This review now turns to examining the concepts and mechanisms to which Charities can often be subject to related to their Transparency and Accountability.

This section explores Transparency and Accountability in the context of Charities. This is done so that we may understand the mechanisms by which these organisations may become more trustworthy to their stakeholders, facilitating not only their daily operation (as discussed above) but in doing so; continue producing value for society at large. In understanding the roles that organisational Transparency and Accountability may play in this, we situate the research as operating within these spaces in order to provide a foundational understanding from which to begin working.

Transparency and Accountability are seen increasingly desirable in governments and organisations (Hood, 2010; Oliver, 2004; Heald, 2003). Oliver states that Transparency has “moved over the last several hundred years from an intellectual ideal to centre stage in a drama being played out across the globe in many forms and functions” (Oliver, 2004, p.ix). Corrêa et al. say Transparency and Open Government is “synonymous with efficient and collaborative government” (Correa et al., 2014, p.806), and Steele goes as far to say “Transparency is the new `app’ that launches civilization 2.0” (Steele, 2012, p.70). Non-Profit Organisations (NPOs) in the UK are held to stringent Transparency standards by an organisation known as the Charity Commission, which is responsible for registering and regulating charities in England and Wales “to ensure that the public can support charities with confidence” (UK Government, 2021c). The development of trust is foundational in the relationship between an organisation and those invested in its activities or performance, known as stakeholders, which is compounded by the notion that a stakeholder in an NPO might not be in direct receipt of its services (MacMillan et al., 2005; Krashinsky, 1997). Beyond this, Accountability is seen as a way of building legitimacy as an organisation (Anheier & Hawkes, 2009). Watchdog organisations such as the Charity Commission and others therefore play an important role in developing stakeholder relationships with NPOs through Transparency measures, making them accountable to those invested in them. Oliver writes that NPO expenditure is often the most “emotional”, and a person’s decision to invest in a charity will be down to how comfortable and confident they are in its operation (Oliver, 2004).

Hood writes that “Transparency is more often preached than practised [and] more often invoked than defined” (Hood, 2006, p.3). This section considers various definitions of Transparency in relation to the UK Charity Commission, NPOs, and the measures that are taken to make them accountable to stakeholders. It also inspects Transparency’s synonymity with Accountability.

As noted, the attributes of Transparency and Accountability are viewed as traits which are increasingly important and attractive traits in governments and organisations, and have moved over the last century from intellectual ideas in the wings to playing a central role across the globe (Oliver, 2004). Corrêa et al say of Transparency and Open Government that it is “synonymous with efficient and collaborative government” (Correa et al., 2014, p.806), and Steele writes that “Transparency is the new app that launches civilization 2.0” Steele (2012). However, the terms are still ambiguous. Hood writes that Transparency is “more often preached than practiced [and] more often invoked than defined” (Hood, 2006, p.3). This section therefore aims to explore various definitions of ‘Transparency’.

According to Meijer, Transparency was historically inherent in the actions and interactions of everyday society since, in “traditional societies” (sic), the density of social networks made one’s actions highly visible (Meijer, 2009). Meijer contrasts this with modern societies where “people do not know each other – many people in cities do not even know their neighbours” and argues that societies which operate at a larger scale suffer a decline in social control, which calls for new forms of Transparency that match the scale of the society (Meijer, 2009, p.261). The term Transparency has been a watch-word for governance since the late 20th century, yet its roots stretch back much further. Hood identifies three ‘strains’ of pre-20th-century thought that are at least partial predecessors to Transparency’s modern doctrine: rule-governed administration; candid and open social communication; and ways of making organisation and society ‘knowable’ (Hood, 2006).

The first of these “strains” of thought, Rule-governed administration, is the idea that government should operate in accordance to fixed and predictable rules and Hood calls it the “one of the oldest ideas in political thought” (Hood, 2006, p.5). This notion may be summarised effectively with the platitude of “a government of laws and not men”, where the laws are stable and governing is thus not subject to the discretionary attitudes of individuals. The second strain, Candid and Open social communication, had its early proponents liken Transparency to one’s “natural state”, and it saw an implementation in the ‘town meeting’ method of governance where members of the town would deliberate in the presence of one another – making all deals transparent and ensuring all parties were mutually accountable (Hood, 2006). The third of form of proto-Transparency doctrines, is the notion the social world can be made ‘knowable’ through methods or techniques that act as counterparts to studying natural or physical phenomena. Hood describes an 18th-century “police science” which exposed the public to view through the introduction of street lighting or open spaces, as well as the publication of information (all of which designed to help prevent crime) (Hood, 2006).

When viewed in this historical context, from these different perspectives, it can be said that Transparency is inherently concerned with information; access to it, and effective use of it. Oliver describes Transparency as having three key components: something (or someone) to be observed; someone to observe it; and the means supporting such an observation (Oliver, 2004). Heald discusses how these first two components can manifest in modern Transparencies with a property of directionality; a direction being an indicator of who is visible to whom (Heald, 2006). Heald conceptualises four directions of Transparency that exist across two axis: Upwards and Downwards; Inwards and Outwards (Heald, 2006).